Vision and Rationality in Comic Books pt. 1 & McCloud Ted Talk

|

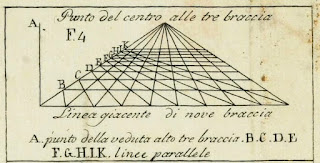

| from Alberti's De Pictura-- a boring book that explains that how we see the world depends on our position. |

Ahhh, aesthetics. I forgot to mention in my last journal entry outlining what I like about comics and graphic novels is the genre's intersections with aesthetics (and, also, linguistics, cultural studies, visual art, etc.). But regarding aesthetics: so much of my studies in grad school have focused on challenging myself (and others) to reexamine the world with a different gaze. How does phenomenology and lived experiences alter our perceptions? In this case, graphic novels and comic books present us with a hybrid of prose juxtaposed again a visual medium that attempts to employ all of the reader's senses. Combine this with the "low culture" aspect and wider publishing opportunity, I spoke of in my previous entry, creates a perfect platform to examine vision and rationality.

DeFrain assigned us Scott McCloud's 2009 Ted Talk which discusses the artist's personal history with both comics and the study of comics, along with the importance of vision within the genre. McCloud highlights the importance of vision without rationality (the importance of the unseen within a scene) in both the creation of comic books as well as our consumption of the medium. Comics are not animated and rely on the reader's active participation. Comics also lack the book's form-- our brains are hardwired to read from left to right, but the reader must follow the writer's consciousness to process meaning. How does our mind create a spatial/temporal plane established only by sequential paneling?

Take for instance these two sequences from Alison Bechdel's Fun Home.

The first sequence is pretty standard and traditional; it is meant to be read from left to write and then top to bottom. The second however, has a much looser structure and relies on the reader to interact with the "fun home's" physical/natural structure to parse the separate characters' identities and relationships amongst one another.

McCloud also brought up four different "types" of comic book perceptions. They are as followed:

- Formalist: attempting to understand structure and nature

- Classicist: celebrating beauty and craft

- Animist: searching for transparency

- Iconoclast: establishing authenticity

One of my aims for this course is to try and categorize the works that we encounter. So far, we've only read Kirkman and Moore's The Walking Dead: Days Gone Bye (1.1). While the series is deeply rooted in dystopian sci-fi/horror genre, the illustrations and structure of the work seems to be entrenched in what McCloud views as formalist.

The last aspect that McCloud discusses in his talk reviews the role comics play in 21st century/digital society. McCloud recounts the early days of the web, referencing the late 90s and says that comics began to make the same mistake all mediums face in times of innovation: appropriating the medium's previous form and structure. Thusly, early web comics attempted to follow the conventions of printed comics, where McCloud argues they should have attempted to expand their form. McCloud ends by highlighting circular narratives that are achieved by the ability to "scroll" on a computer.

I touched upon this briefly in my last journal entry, claiming that comics have a DIY/punk sensibility about them which I (and I assume many others) find so alluring. So much of what I read is distributed via an online medium and self publishing. I'm lucky to have several close friends who write and draw comics, and I'd like to discuss with them the appeal of this practice. Alas, that is a journal entry for another day.

-JA

Comments

Post a Comment